Renata’s Diary

July 21, 1883 Oh dear God help me for all that I am living through! This is how it happened that Antonie came here to the convent and kidnapped me and took me and Señora to San Francisco. And no, we are not home yet!

Mother Yolla had chosen me for a whole week of lunch duty, because she said cooking “suited” me, so there I stood on Friday morning in the kitchen, patiently chopping a large onion, dropping the pure white slices into the hot sputtering oil.  I hummed to myself, and my thoughts turned to the falseta I had been strumming the night before on the guitar, and I had a flash out of nowhere of the altar, and the large silver cross that keeps watch over the chapel. And then once again I was back in the kitchen, mindlessly pushing the wooden spoon through the sizzling onions, mixing them together with the tiny slivers of garlic that had already turned golden and crisp at the bottom of the cast iron pan.

I hummed to myself, and my thoughts turned to the falseta I had been strumming the night before on the guitar, and I had a flash out of nowhere of the altar, and the large silver cross that keeps watch over the chapel. And then once again I was back in the kitchen, mindlessly pushing the wooden spoon through the sizzling onions, mixing them together with the tiny slivers of garlic that had already turned golden and crisp at the bottom of the cast iron pan.

I hummed to myself, and my thoughts turned to the falseta I had been strumming the night before on the guitar, and I had a flash out of nowhere of the altar, and the large silver cross that keeps watch over the chapel. And then once again I was back in the kitchen, mindlessly pushing the wooden spoon through the sizzling onions, mixing them together with the tiny slivers of garlic that had already turned golden and crisp at the bottom of the cast iron pan.

I hummed to myself, and my thoughts turned to the falseta I had been strumming the night before on the guitar, and I had a flash out of nowhere of the altar, and the large silver cross that keeps watch over the chapel. And then once again I was back in the kitchen, mindlessly pushing the wooden spoon through the sizzling onions, mixing them together with the tiny slivers of garlic that had already turned golden and crisp at the bottom of the cast iron pan. A cloud of onion fumes rose into my eyes (I write this here and can still feel the sting of the tears). I set three red peppers on the wooden cutting board, and prepared to slice them along their length, Teresa appeared, carrying a pile of plump green chiles in her garden basket. She added a couple green chiles to my pepper pile, turned and disappeared into the garden again.

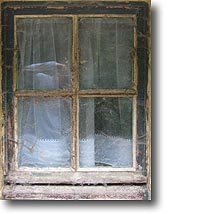

A second cloud of onion rose up, and this one got my tears flooding, and at first I tried mopping them on the sleeve of my habit, but finally, as the tears wouldn’t stop, I pulled my long white apron up to cover my face. Holding the cotton apron in two hands, I began laughing, thinking, here I am crying over one large onion in a frying pan. But when I dropped the apron, my laughter vanished, because there filling the small window in the pantry behind the kitchen was Antonie’s wilted face. As he was pressed up close against the wavy glass, his features were distorted. He looked more ghastly than I had ever seen him look before.

Where had this sad specter of a man come from? Certainly he wasn’t supposed to be here, he was never ever supposed to appear at the convent, that much he knew as well as I did. Antonie himself had told me repeatedly that Father Ruby had clearly forbidden him entry. When I asked why, Antonie replied that at some time, he would explain “every last detail” of the arrangement that he had with Father Ruby regarding me; but indeed, I had been told this much: he was forbidden at the convent, which explained why I always went to visit him.

But here now was his face flushed and streaked and red, pasted against the crosspole of the window. He looked all the more odd, divided as he was into four window panes. At first it looked to me as though he had been running, because his skin was shiny with sweat, and his long black hair was slicked to his head and his black hat dangled on his back by the leather strings tied at his chin. He was open-mouthed and breathing hard, and in his eyes was a tired, sallow look. He met me at the door.

“Why have you come?” My voice quivered. I had opened the door no more than a crack, and I was whispering and trembling. I was a mixture of amazement and anger and fear and something else too, something I couldn’t identify clearly, but it too was crawling all over me. Antonie took one step forward, and wobbled there, barely able to place the square toe of his boot against the door, and his face swerved forward to the opening, and I could see the remote look in his eyes.

Suddenly he lifted his hand and he bit hard, desperately, into his own knuckles. His eyes shone large and empty and glossy. He raised one hand up, and he braced his open palm against the doorframe, and he gasped for breath. Looming there, his arm arched over me, he scared me. He trembled, and those eyes of his bored into me.

“I want to ask…I must ask that you accompany me,” he wheezed, and I was already shaking my head before he finished, in complete and utter amazement and disbelief, that he was here, that he was asking something that I clearly could never do. All the time I stared at him I was aware of those liquid black eyes on me, eyes that looked like they had been ladled out of death. His moist red face was inches from my own, and the smell of his breath was rotten.

“You…must be crazy, that’s impossible,” I said, and thought then in a great rush that he would indeed prove to be the death of me, or certainly the dishonor. “You know that I cannot think of such a thing, and that you could even imagine it, or propose it.”

“Listen,” he demanded, and despite his exhaustion, he maintained his imperious stare. His eyes opened wider still. “I will explain. I have Senora with me. I have also hired a coach and a driver, for your…for all of our comfort. I need you to come with me to see the specialist in San Francisco. We leave immediately.”

He had spoken before of this doctor. We had discussed his worsening condition, the syphilis, how he would need to see someone with skills beyond those of the local physician.

“But I am in no position to go, not now, not ever, you must know that,” I said, letting the door swing open a little wider, and with that, he stumbled forward and he grabbed onto me.  And the two of us back stepped inside. The frying pan sent up its woeful steam of onions, now turning black. The noonhour was quickly approaching and the nuns would be clamoring for lunch, or as Mother Yolla called it, “our midday repast.” Meanwhile, here was Antonie straddling over me, barely able to stand up.

And the two of us back stepped inside. The frying pan sent up its woeful steam of onions, now turning black. The noonhour was quickly approaching and the nuns would be clamoring for lunch, or as Mother Yolla called it, “our midday repast.” Meanwhile, here was Antonie straddling over me, barely able to stand up.

And the two of us back stepped inside. The frying pan sent up its woeful steam of onions, now turning black. The noonhour was quickly approaching and the nuns would be clamoring for lunch, or as Mother Yolla called it, “our midday repast.” Meanwhile, here was Antonie straddling over me, barely able to stand up.

And the two of us back stepped inside. The frying pan sent up its woeful steam of onions, now turning black. The noonhour was quickly approaching and the nuns would be clamoring for lunch, or as Mother Yolla called it, “our midday repast.” Meanwhile, here was Antonie straddling over me, barely able to stand up. His heavy boots clattered on the kitchen floor. And he filled the room with his height, and with his foul smell. I caught another glance of those pained, brooding eyes. He was, to my way of seeing, a swarm of dark clouds hovering, threatening a downpour – or more—over my calm morning sky.

“Please, Antonie, please, you must leave, you must go, now, you know that, please, before anyone discovers you, because if you are here, I don’t who knows what could happen to me, I’m not sure what Mother Yolla will do, but the two of them, please…” I managed to push him away.

He swayed, and took hold of the wall. I raised my apron in both hands and twisted it. I thought of trying to hammer him with my fists, because I was so angry, but I was much more afraid to touch him, as he listed so weakly.

His mouth opened twice before he got the next words out. “My dear Renata, pl…ease pl…ease cousin.” He whispered and leaned forward as he did, so that I could smell that fetid warm breath. Then he bent his head slightly to one side. “”Father Ruby…likes me,” he said, a queer smile spreading across his lips. A glaze of sweat lay there too. “

And he is most urgently concerned about my…health. The good father… needs me, my…” Here he started coughing. His head came forward and when he raised his face again, I was horrified to see a paste of blood on his chin. He leaned forward again and forced his words out, between gasps.

“You see, he…Father… Ruby is most concerned that I continue my…my donations.” Here Antonie paused and then lifted the back of his hand to the side of my face. I shuddered. And then he uttered four words that I wish I had never heard.

“He insists…you go.”

With this, Antonie swiveled and sank to the floor. Here was the man who once commanded whatever he willed, who thrilled in his own power, who delighted in satisfying his every desire, who dictated even to the likes of our own priest and master .

I cried out to see him so pathetic.

At that moment, Senora’s face appeared at the pantry window, and seeing Antonie, she rushed in. Her face. Lined. And worn.

And behind her. Father Ruby. Giving me a look that I will never forget: something I can only call primitive, he motioned to the two of us to help him lift Antonie up. And as the onions turned to blackened wisps on the stove, and then to char, the three of us dragged Antonie to the grey wagon. And lifted him to a pile of blankets on the back.

As we set off, I turned to see Father Ruby pivot and retreat into the rectory. Rage flooded me and so too, did utter hatred, and then I reigned in both emotions: this was no way to feel toward the priest. God was almost certain to punish me for my despicable thoughts. But in my heart, I could see. He was simply a despicable old man.

My eyes filled and I closed my hands around my face. Senora murmured something to try to comfort me. But I would not be comforted. For there I was, still in my apron, and with the odor of the kitchen onions still clinging to my hair. I had not a stitch of extra clothing with me, not even a cape or my shawl, and I was off for who knew how long to God knew where.

But no sooner did I feel a chill than Senora patted my hand and I saw that she carried for me the blue silk shawl, all covered in flowers, and dripping in long fringe. “Un rebozo,” she murmured wrapping my shoulders and that just made me cry harder.

She began to hum something. Ah. But it was the same lament that Antonie liked to strum on his guitar. That music just played more cruelly on my mind and I cried harder.

“No más,” I said. And so she stopped. But the tune kept up for hours in my head as we drove over the bumpy roads. The music coiled and coiled there, reminding me of my poor mother, and her untimely death, and the childhood that I never had.

“He insists…you go.”

With this, Antonie swiveled and sank to the floor. Here was the man who once commanded whatever he willed, who thrilled in his own power, who delighted in satisfying his every desire, who dictated even to the likes of our own priest and master .

I cried out to see him so pathetic.

At that moment, Senora’s face appeared at the pantry window, and seeing Antonie, she rushed in. Her face. Lined. And worn.

And behind her. Father Ruby. Giving me a look that I will never forget: something I can only call primitive, he motioned to the two of us to help him lift Antonie up. And as the onions turned to blackened wisps on the stove, and then to char, the three of us dragged Antonie to the grey wagon. And lifted him to a pile of blankets on the back.

As we set off, I turned to see Father Ruby pivot and retreat into the rectory. Rage flooded me and so too, did utter hatred, and then I reigned in both emotions: this was no way to feel toward the priest. God was almost certain to punish me for my despicable thoughts. But in my heart, I could see. He was simply a despicable old man.

My eyes filled and I closed my hands around my face. Senora murmured something to try to comfort me. But I would not be comforted. For there I was, still in my apron, and with the odor of the kitchen onions still clinging to my hair. I had not a stitch of extra clothing with me, not even a cape or my shawl, and I was off for who knew how long to God knew where.

But no sooner did I feel a chill than Senora patted my hand and I saw that she carried for me the blue silk shawl, all covered in flowers, and dripping in long fringe. “Un rebozo,” she murmured wrapping my shoulders and that just made me cry harder.

She began to hum something. Ah. But it was the same lament that Antonie liked to strum on his guitar. That music just played more cruelly on my mind and I cried harder.

“No más,” I said. And so she stopped. But the tune kept up for hours in my head as we drove over the bumpy roads. The music coiled and coiled there, reminding me of my poor mother, and her untimely death, and the childhood that I never had.